Tremendous Progress: When Education Data Starts Talking Like Trump

On the last official day of the school year, while teachers are closing classrooms, shutting laptops, and limping toward summer, an email lands from the Minister of Education.

It is warm.

It is grateful.

And it is overflowing with numbers.

Not just any numbers. Encouraging numbers. Winning numbers.

We are told that phonics achievement has leapt from 36% to 58%. That students in a maths trial made up to two years’ progress in just 12 weeks. That even those not in the trial made gains of up to a year. That the Ministry itself says expectations were exceeded.

It’s a victory lap, complete with festive sign-off, delivered precisely when scrutiny is least likely.

If the tone feels oddly familiar, it’s because this style of communication isn’t about education at all.

It’s about political performance.

The Trump Playbook, Education Edition

Donald Trump didn’t invent selective data, but he perfected a way of talking about it:

Pick a narrow metric

Announce it loudly

Use superlatives instead of context

Cite unnamed authorities

Declare victory early

Move on quickly

Sound familiar?

Translated into Trump-speak, the Minister’s email might read something like this:

“Nobody’s ever seen phonics like this before. Tremendous phonics. Up from 36 to 58 percent. People said it couldn’t be done. The Ministry? Shocked. Totally exceeded expectations. Our maths? Incredible. Two years of progress in 12 weeks. Could’ve been more, honestly. We’re winning so much at education you’re going to get tired of winning.”

Satirical, yes.

Unfair? Not really.

Because no serious educator would present data this way without caveats, especially when:

phonics ≠ reading

assessments have changed

cohorts are selective

“up to” hides variation

timelines are compressed

methodologies are unexplained

This isn’t transparent reporting.

It’s headline engineering.

“Up To™”: The Most Important Phrase in the Room

“Up to two years’ progress.”

“Up to a year of gains.”

“Exceeded expectations.”

These phrases aren’t lies, they’re political tools. They invite the reader to imagine best-case outcomes while quietly ignoring distributions, baselines, and outliers.

Trump used this constantly:

“Many people are saying.”

“Record numbers.”

“The best ever.”

Which people?

Which records?

Compared to what?

In this email, the data is presented as settled fact rather than provisional evidence. The debate is closed before it begins.

Same Script, New Audience: Parents

On the same day, the Minister appears in a video speaking directly to parents:

“Great news for parents. You told us that you wanted to be able to help your children with their mathematics more at home… You told us that you wanted to help out more at home and we’ve delivered.”

No data this time.

Just reassurance.

A new maths practice tool, delivered via an international platform, will be available next week. It’s aligned. It’s practical. It will help children feel good about their abilities.

Enjoy.

This is the same messaging architecture, just tuned for a different audience.

To teachers: “The data proves it’s working.”

To parents: “You asked. We delivered.”

Different language. Same move.

Declare success

Present decisions as inevitable

Skip the messy middle

Keep the story positive

The Politics of “You Told Us, We Delivered”

“You told us, and we delivered” is a powerful phrase. It implies consultation, responsiveness, and closure, without ever explaining:

what alternatives were considered

who made the decision

how procurement occurred

why this platform, not local solutions

how success will be evaluated

It turns a complex policy choice into a feel-good transaction.

Trump did this constantly:

“The people wanted it. I listened. We delivered.”

Once framed this way, questioning the decision sounds like opposing parents, or children, or success itself.

That’s not engagement. That’s narrative insulation.

Timing Is the Tell

None of this arrives mid-year, alongside published methodologies.

It arrives:

on the last day of term

at the start of the holidays

just before parents log off

By the time schools return, the story is already set:

The reforms are working. The tools are here. The debate is over.

Trump rarely waited for full evidence before declaring victory. The victory was the message.

Why This Should Worry Us

This isn’t about personalities or party politics.

It’s about what happens when education communication starts to prioritise confidence over clarity, optimism over evidence, and affirmation over explanation.

Education depends on:

trust

nuance

professional scepticism

long-term thinking

Not slogans.

Not victory laps.

Not end-of-term emails packed with uncontextualised wins.

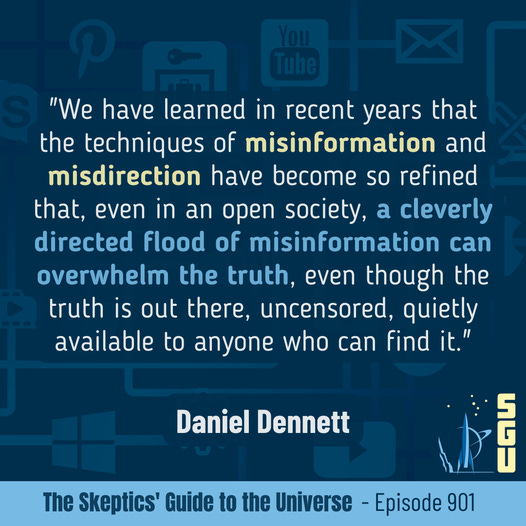

When data starts talking like Trump, it stops informing and starts persuading.

And in education, persuasion without transparency isn’t leadership.

It’s theatre.

Curious about the work I do in education around the world?

I’m currently working alongside educators and systems in Australia, Canada, Finland, the UK, Nigeria, India and Singapore, sharing learning, supporting innovation, and advocating for what truly matters in education: people, purpose, and professional trust. If you’re interested in where I’m travelling, who I’m working with, or how this work might support your own context, here’s where you can learn more:

Professional Speaker Profile – Keynotes, consultancy and facilitation

P-BLOT™– Evidence-informed support for behaviour and learning

Connect on LinkedIn – Reflections, resources and current projects

Solid breakdown of how selective data presentation works. The "up to" framing is brutal once you see it – it technically allows for any distribution where at least one student hit the max gain, which could mean most kids saw way less. I've reviewed enough education pilots to know that when methodology details are missing and numbers are announced at holiday timing, someone upstream made acalculation about attention spans. What bugs me is the opportunity cost: parents who actually want to support learning at home get handed a platform without the context to judge whether it solves their kid's actual bottlenecks. If the phonics gains are real and sustained, great – but the way it's communicated undermines rather than builds the trust needed for harder conversations down the road when results are mixed.

Thanks for this article. This has been niggling at me too. The data tells us children learned the skills that were taught. That’s encouraging. What it doesn’t yet tell us is whether those skills lead to stronger reading and writing over time. That’s not an attack on teachers or families - it’s the next question any serious education system should ask.