What Happens to the Scientist in Your Child?

How the New Science Curriculum Risks Unteaching Curiosity

The Scientist You Already Know

If you’ve ever watched a four-year-old crouch over a puddle, mixing mud with a stick and whispering, “I’m making soup for the worms,” you’ve seen a scientist in action.

They notice patterns, test ideas, make predictions, observe results, and share discoveries with joy.

That’s science — alive, sensory, relational.

Under Te Whāriki, our early-childhood curriculum, this kind of exploration is the heart of learning. Skilled teachers design experiences that help children notice, test, and reason. They scaffold curiosity through conversation, questioning, and deliberate modelling. A good ECE or junior teacher doesn’t “let children work it out on their own” — they shape learning through guided inquiry, moment by moment, responding to what children show and say.

Te Whāriki grows scientific thinking through curiosity — not through content alone, but through the courage to wonder, to get messy, and to ask “why?” a hundred times a day.

A Big Shift at School

When that same curious child walks into school next year under the 2025 Science Curriculum, the tone changes.

Science becomes a discipline — a subject to be measured and mastered.

By Year 3, children are expected to:

Explain that the Earth spins on its axis and orbits the Sun.

Describe shadows as evidence of the Sun’s position.

Know that the Earth is “roughly spherical.”

Recognise that Aristotle proposed this idea around 2,300 years ago.

And in biology?

They’re to learn that Theophrastus — another ancient Greek, born before 300 BCE — “described plant forms and structures, and his botanical texts were used for centuries.”

At five, six, and seven, our children are moving from hands-on science to historical recall.

Instead of investigating why the Sun appears to move across the sky, they’ll be told who first wrote about it.

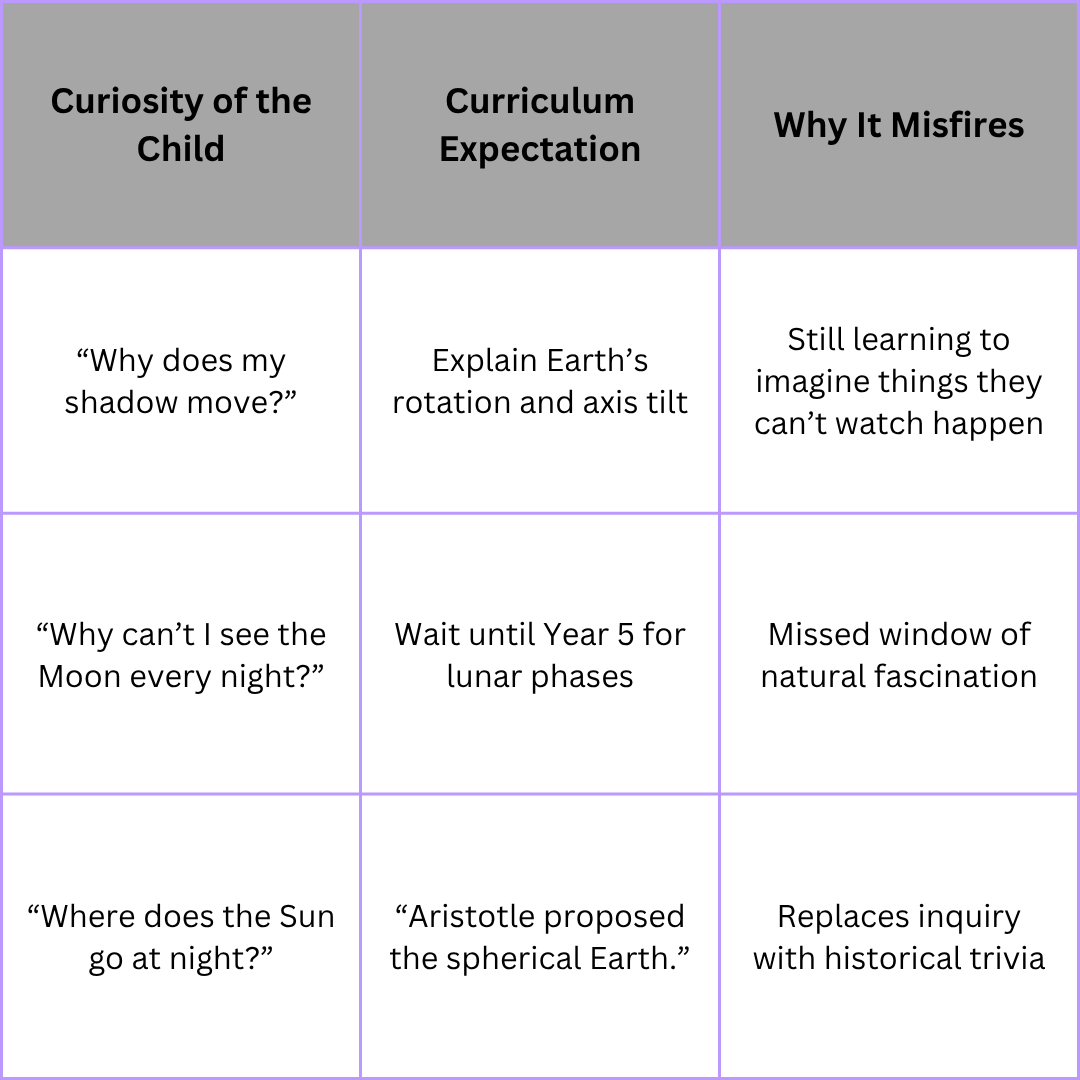

When Knowing Replaces Noticing

It sounds impressive — grounding science in its history. But for a five-year-old, this is developmentally meaningless.

Skilled teachers already use children’s questions as starting points for structured inquiry:

Why does my plant lean toward the window? What makes shadows grow?

Through dialogue, observation, and language, teachers connect those questions to scientific ideas about light, energy, and growth.

That’s rigorous science — guided, evidence-based, and intentional.

But when the curriculum asks for the names of ancient scientists before it allows those investigations, we lose the teachable moment where curiosity becomes understanding.

At five, a child doesn’t need to remember Theophrastus.

They need a teacher who helps them see how sunlight makes a seed turn toward the light.

Why the Sun Has to Wait

Here’s something few parents realise: the new curriculum restricts Earth-and-Space Science until Year 3.

That means for the first two years of school, children won’t formally explore the very things that most capture their imagination — the Sun, the Moon, the shadows that move across the playground.

Only in Year 3 do they begin learning that:

“The movement of the Earth in relation to the Sun causes observable patterns — the rising and setting of the Sun, the length of a day and a year. The Earth is roughly spherical and rotates on its axis once every 24 hours.”

To an adult, that sounds logical. To a five-year-old, it sounds like a riddle.

Because at that age, learning isn’t abstract — it’s lived. They feel the Sun on their skin. They see their shadow stretch and shrink. They notice that the Moon changes shape.

These are golden scientific moments — the foundation of later understanding. When teachers trace shadows, record the sunrise, or talk about the Moon’s cycle, they’re not “doing play.” They’re teaching observational science — the groundwork of evidence-based reasoning.

But by formalising these ideas only at Year 3, and framing them in technical language — rotation, axis, sphere — the curriculum risks skipping over the very experiences that make those ideas meaningful.

Developmental Misalignment

We’re giving children language before experience, and answers before questions.

Where Did the “Understand” Go?

You might hear teachers talk about the “Understand–Know–Do” framework — it’s meant to balance thinking, knowing, and doing.

That’s how Te Mātaiaho was written, the curriculum prior to the proposed documents introduced this week. That children learn what to know, what to do, and most importantly why it matters.

But the new Science Curriculum has quietly dropped the understand part.

It still tells children what to know and what to do — but not why they’re learning it, or how it connects to their world.

When “understand” disappears, so does the space for wonder.

The science of feeling the wind, noticing shadows, asking why the Moon moves gets replaced by the science of remembering who said what, and writing it down correctly.

This subtle change shifts science from sense-making to fact-making.

It moves from helping children build meaning to making them recall meaning that’s already been decided for them.

And when teachers are measured by coverage and accuracy rather than connection and curiosity, they lose permission to linger in that moment when a child says, “Look — the sky’s pink!”

That moment is science too.

The Fine Print: What the Curriculum Says vs. What It Does

At the front of the 2025 Science Curriculum, the message sounds reassuring:

“In Years 0–3, teachers support students to begin observing and describing their surroundings, fostering foundational scientific knowledge and curiosity through direct, hands-on experiences… sensory exploration, concrete thinking, and communication grounded in facts and evidence.” (p.5, 2025).

That sounds beautifully aligned with Te Whāriki and Te Mātaiaho - a promise of muddy hands, wide eyes, and wondering minds.

But then you turn the page to the actual learning strands, and the picture changes:

In Physical Science, children “investigate how shape affects movement” and “compare how pushing or pulling changes motion.”

In Biological Science, they “identify parts of the body related to senses” and “recognise Theophrastus as the founder of botany.”

In Earth and Space, they “describe how Earth’s rotation causes day and night” and “recognise Aristotle as proposing a spherical Earth.”

These strands are content-heavy and adult-centred. They sound more like miniature versions of secondary-school science than invitations to explore.

The curriculum says it values curiosity, but the fine print tells another story.

It promises mud, movement, and hands-on discovery — then replaces them with diagrams, definitions, and dead scientists.

It talks about observation, but what it really measures is recall.

And while our five-year-olds are still learning through their fingers, the curriculum is already asking them to think like little physicists.

The Side-Effects of “Growing Up Too Fast”

When learning moves too quickly into the abstract, the side effects ripple across the whole child:

Curiosity shrinks. When there’s one right answer, wondering loses its power.

Confidence dips. Children who once asked everything stop raising their hand.

Creativity narrows. Open play gives way to worksheets and textbooks.

Belonging weakens. The local sky and landscape - te taiao - disappear behind textbook diagrams.

In short: the curriculum that set out to teach science may end up unteaching curiosity.

What Real Science Looks Like in Childhood

Real science in the early years isn’t chaotic or unstructured. It’s responsive, intentional, and precise. Teachers plan experiences that provoke questions, guide children to observe systematically, model how to record and compare, and use rich language to connect experiences to emerging concepts.

When a teacher helps children explore floating and sinking, they’re not “letting them play” - they’re building the foundations of density, buoyancy, and material properties.

When they invite children to watch shadows, they’re teaching about light, time, and perspective.

The difference is that the child’s body and senses are part of the experiment: learning is lived before it’s labelled.

This is robust teaching, not loose exploration.

It’s the kind of science education that honours both the intellect and the imagination.

How Parents Can Help

Protect the questions.

When your child asks “why,” answer with “what do you think?” before explaining.Keep play alive.

Science starts with play. Shadow-tag, garden experiments, puddle measuring -these are data sets in disguise.Value noticing over naming.

Your child doesn’t need to know Aristotle or Theophrastus. They need to know their backyard sky.Ask schools how curiosity is guided.

Great science teaching doesn’t mean letting children drift; it means helping them connect experience to explanation with the right balance of guidance and freedom.Trust that wonder is rigorous.

Every scientist was once a child who asked too many questions.

Every scientist began as a child who wondered where the Sun went at night.

Te Whāriki and Te Mātaiaho understand this. They don’t say “let children find it out.” They ask teachers to notice, respond, and extend - the very definition of rigorous pedagogy.

The 2025 Science Curriculum risks flipping that order: measuring before nurturing, telling before guiding.

Our challenge, as parents, teachers, and community, is to keep that early spark alive.

Because science doesn’t begin in the lab. It begins in the backyard, with a child, a question, and a bit of sunlight.

Curious about the work I do in education around the world?

I’m currently working alongside educators and systems in Australia, Canada, Finland, the UK, Nigeria, India and Singapore, sharing learning, supporting innovation, and advocating for what truly matters in education: people, purpose, and professional trust. If you’re interested in where I’m travelling, who I’m working with, or how this work might support your own context, here’s where you can learn more:

🎤 Professional Speaker Profile – Keynotes, consultancy and facilitation

🧠 P-BLOT™– Evidence-informed support for behaviour and learning

🔗 Connect on LinkedIn – Reflections, resources and current projects

Another great piece Sarah. Thanks for the work you are doing.

Seeds turn towards the light?